Peace efforts need staying power. And peace can never be taken for granted.

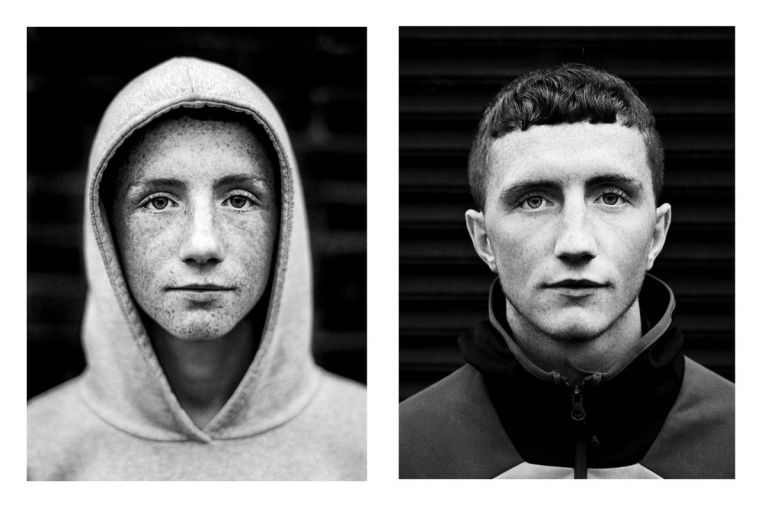

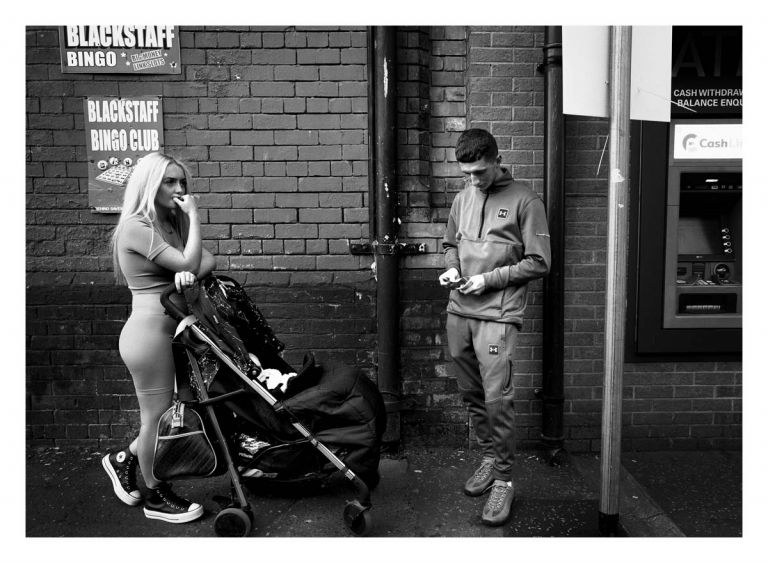

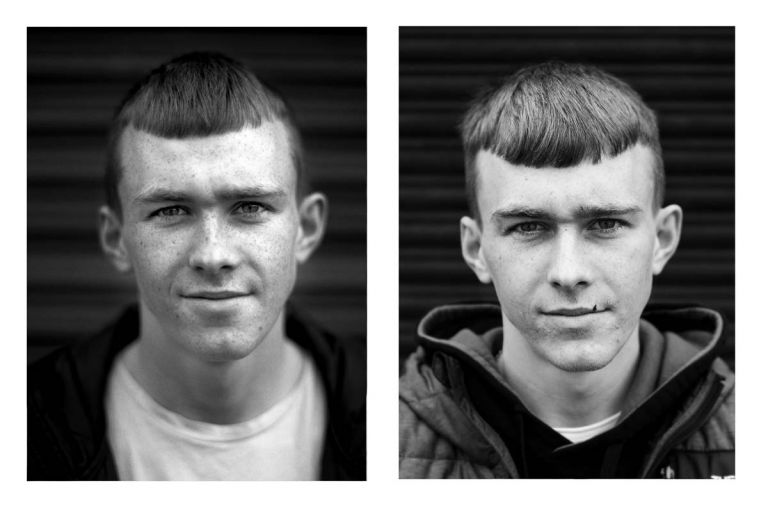

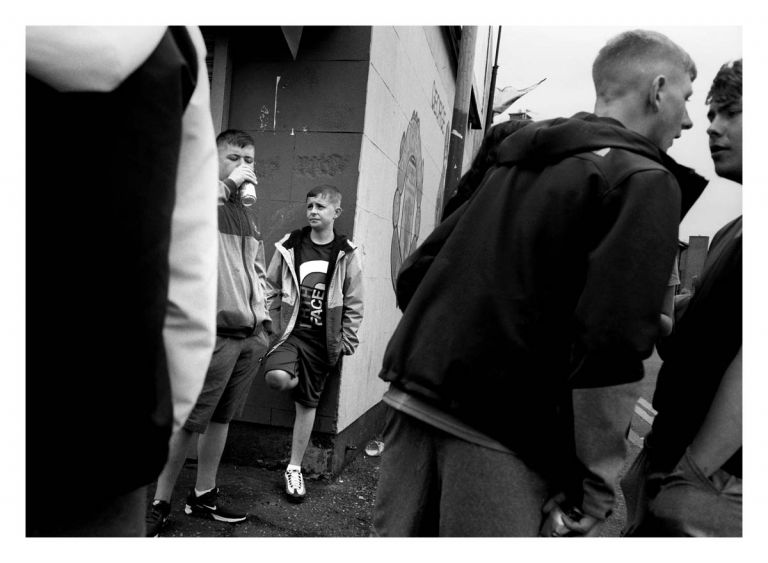

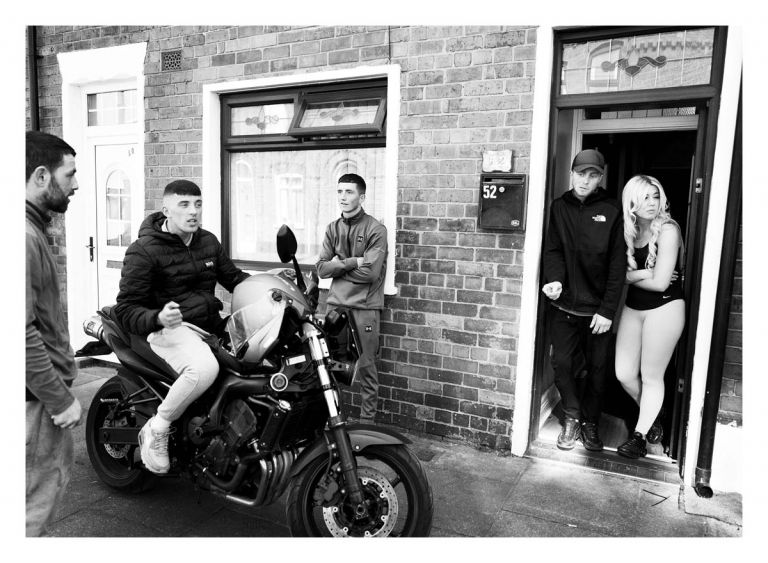

For years I have been accompanying the generation of children born in the working-class neighbourhoods of Belfast after the peace agreement of 1998. Although they never experienced the civil war conditions during the Troubles, there was still little rapprochement between Catholic republicans and Protestant loyalists. They live side by side, still separated by fences and walls, often fighting, rarely with cross-community contacts or even love affairs. Progress was slow, but it was going in the right direction. “We still need one more generation”, I often heard.

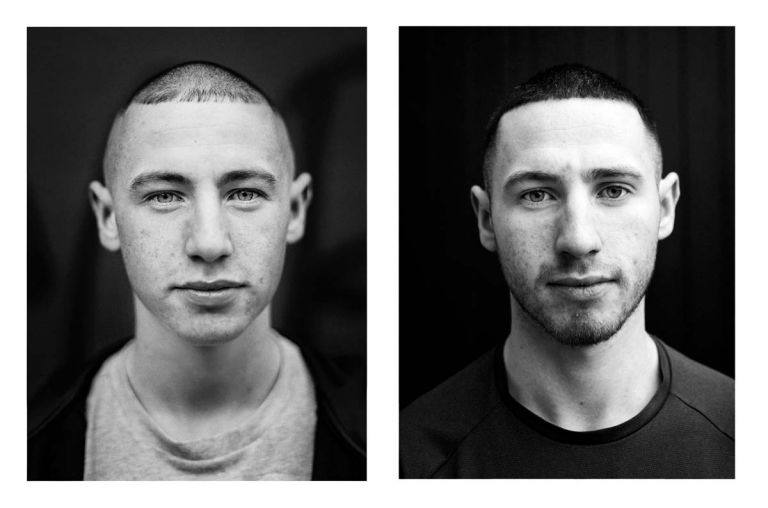

The teenagers of the past are now young adults themselves, have children of their own, most are still around. Some are in prison, some in psychiatric care. The worst and most heart-breaking is that some have committed suicide. Tiernan and Paul have kids, Kieran works in a Youth Club to offer the young people of today more than he got back then. But it is difficult, for many the situation seems more dramatic than it was in 2017. On top of the world’s devastating events such as the Corona pandemic and the war in Ukraine, there is the self-made problem of the Northern Ireland protocol in the Brexit negotiations – and the seemingly insoluble problem of the Irish Sea border. This has shaken the mistrust on both sides in politicians like British Prime Minister Johnson, who cannot fulfil the expectations of the loyalists without endangering the Good Friday Agreement, which is sacred above all to the republicans. He is alternately called the worst thimblerig or clown. And tensions are rising. The historic election victory of Sinn Fein in May also contributes to this, further fuelling a union with the Republic of Ireland – Hope for some, horror for others. It is still difficult for people in Northern Ireland to see chances as well as challenges as common and to detach themselves from history.