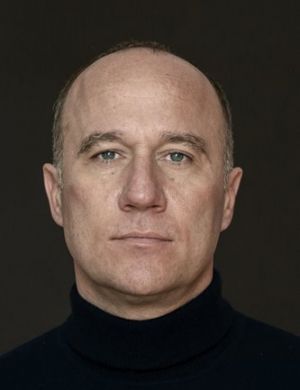

Nicolas Asfouri, Denmark

Photographer Nicolas Asfouri, born in Beirut, is a Danish citizen and started his career in 2001 in London as a freelancer for Agence France Presse, which he joined as a regular member in 2004. In 2016 he became Senior Photographer for the Peking AFP office. Nicolas Asfouri, born into the epicentre of conflict, the Lebanon, is certainly no photographer of flower beds and sunsets. He has reported about Pakistan and Afghanistan, Myanmar and Cambodia, about the tsunami in Japan, about a flood in Thailand. At one time he was about to pack it in, when a friend of his died in Afghanistan in 2014.

But he only stopped as a photographer of war – and now creates photographs on the theme of human rights. Which means: the fight for human rights. Which also means: everything that is not yet peace. But which should lead towards peace. In 2020 his Hong Kong report earned him a World Press Photo Award.

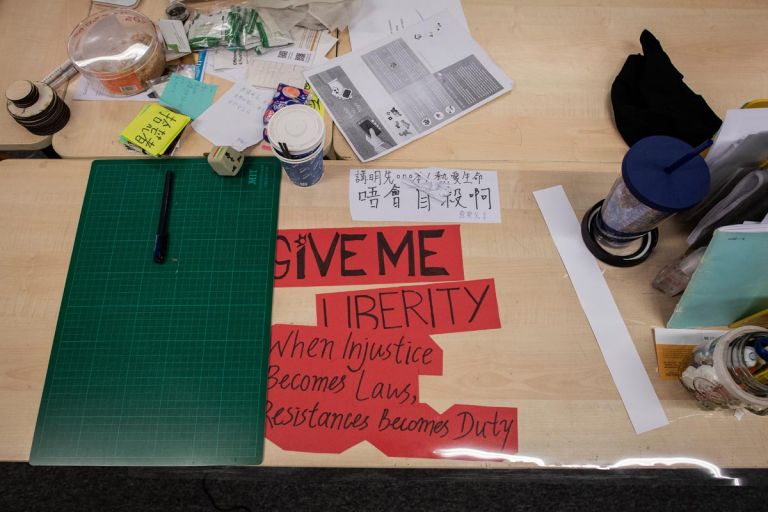

“Give me freedom”, they write on their posters. Or just “Love”. Or “SOS”.

It is the year 2019 in Hong Kong. According to the agreement made between China and the UK in 1997, the former British Crown Colony is already a part of China, but until 2047 it should retain a largely autonomous status: “One country, two systems”. But the ever increasing attempts at a takeover by mainland China in this year 2019 manifest themselves, for instance, in a draft law by Hong Kong’s Chief Executive to facilitate the extradition to the Beijing regime of opponents to the system.

Pupils and students take to the streets against that, young men and women. Then more and more people, a pro-democracy movement, mostly peaceful, in parts militant, ever more brutally suppressed by the police, at first with batons and tear gas, later with live ammunition.

It may not be so easy to understand what we honour in this picture by photographer Nicolas Asfouri. Peace? Hardly. This is not what peace looks like. Certainly not when looking at the photo report by Nicolas Asfouri in total: the pictures of water canons, beaten up, terrified, injured people. Of the knee of a policeman on the neck of a young demonstrator. Of girls with raised hands shortly before they are arrested.

But the girls in school uniform, with the later prohibited masks on their faces, holding hands; the woman, boldly marching through a street with a “Love” sign in her hand; the comforting hugs; the student in a full mall, still holding up his protest poster: If they do not signify peace, they signify a burning desire for it. For a peace that means freedom of opinion and press, freedom from the grip of a party that won’t tolerate opposition. Or at least for a peace that was to be guaranteed until 2047. And that no longer exists even now. (Text by Peter-Matthias Gaede)